Mother to Son by Jasmine Holmes

Jasmine is married to Phil and they have two boys: Wynn and Langston. They’re members at Redeemer.

Jasmine is married to Phil and they have two boys: Wynn and Langston. They’re members at Redeemer.

Wynn, now 4, is named after Wynn Kenyon, who was an Elder at Redeemer in the early days and Phil’s professor at Belhaven. Langston, just 18 months, gets his name from Langston Hughes, an American poet and novelist.

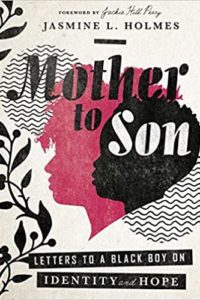

In her new book, Mother to Son, Jasmine writes letters to a black boy about identity and hope as he grows up in this world—and in these times—in a Christian family.

But she’s not writing to just any boy. She writes to a particular boy, to her son Wynn—her “brown-skinned little boy,” her “tall-for-his age toddler who is friendly, exuberant, and loving.” (20)

A masterful storyteller, she tells him his story by starting with her story. She tells him about growing up as a minority in a majority white church and culture, about being Voddie Baucham’s daughter, and about jumping up and down when she first learned he was a boy. She shares her voice and her heart, her joys and her fears, her flaws and her hurts. She’s honest about the mess, and apologies that as her firstborn, he’s a bit of a guinea pig.

“These letters are not a picture of perfect parenthood. They are not the well-crystalize thoughts of a gray-haired, wizened woman. They are the real-time musings of a millennial mama who just tucked you in your highchair for breakfast and begged you for a kiss.” (19)

With each chapter, she lays another brick in the foundation of his identity.

- You are Mine

- You are God’s

- You are Beautiful

- You are American

- You are the Church

- You are More than your Ethnicity

- You are a Brother

- Be a Good Brother to the Sisters

- Be an Advocate

- Be a Bridge

- You are a Different Story

- You are a New Tribe

Her words are intimate and powerful—filled with the fierce tenderness of motherly love. She simplifies complexity and distills truth.

And Wynn’s story is the story of a black boy. Jasmine speaks here with balance and nuance. She brings clarity to confusion, and leads with the gospel.

She tells Wynn about tribalism and politics, about culture and statistics, about complicated heroes and representation, about history and blind spots, about the image of God and the diversity in creation.

Wynn’s identity in Christ and his identity as a black boy are both a part of his story. For Jasmine, one is in the service of the other:

“You are not more beautiful because you are black, but part of your unique beauty comes from the rich heritage that the Lord has woven into your melanin.” (34)

“My little brown-skinned boy, you can’t understand a word of this right now, but I hope you will in time: your skin color will never change your status before Jesus. Full stop. And it’s part of his glorious plan in the unfolding of your story all the same.” (72)

“Your cultural brotherhood is valid.

As long as it is in service of your spiritual brotherhood.” (82)

This is the way forward. This mother wants her son to form a new tribe, that’s really not new at all, but “a return to biblical standards for brotherhood that trumps cultural fragmentation every time.” (148)

But these letters aren’t just for Wynn. They’re meant for us.

May we build bridges, upend tribalism, and listen to one another—for the sake of gospel and the building up of the church.