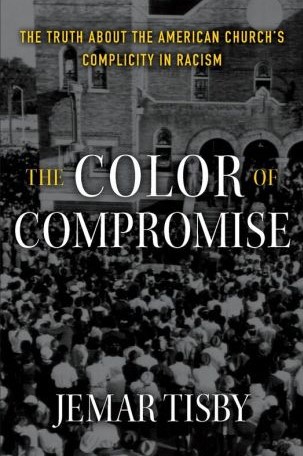

The Color of Compromise, by Jemar Tisby

Would you rather tinker or follow a pattern?

There are two types of Lego users. Some want to follow a pattern to recreate the exact image on the Lego box. Others want to use their imagination to build whatever they desire. Same blocks, two different ways to approach them. This is a helpful analogy to consider as I read The Color of Compromise.

The Bible gives us a clear picture of what life should look like under God’s rule. Revelation 7:9, Ephesians 2:14, Mark 11:17, Genesis 1-2, John 17 show the dignity of all men created in the image of God. They show a picture of equality and unity in diversity. Yet, the founders of our country (and many in our very day) rejected this Biblical pattern and willfully chose to use their sinful imagination, free expression, and power to build an America of their own minds. Using unbridled free expression, power, and imagination can be exciting when it comes to Legos; it’s awful when it comes to laying the groundwork for a diverse country.

Jemar reminds us that American racism, as we know it, was not inevitable. “In the early days of European contact with North America (1500-1700), the racial caste system had not yet been developed. Race was being made at that time. There is no biological basis for the superiority or inferiority of any human being based on the amount of melanin in her or his skin. The development of the idea of race required intentional actions of people in the social, political and religious spheres to decide that skin color determined who would be enslaved and who would be free.”

In the remaining chapters, Jemar shows that a three-fold chord (social, political, religious) was braided together, and it has been difficult—even humanly impossible—to break apart. He shows that the war over race was not simply fought on battlefields by soldiers, but was also fought by pastors and parishioners, by judges and politicians, in congregational and denominational meetings, in courtrooms and churches, with overt and covert laws, in city planning, and in our constitution. He supports this premise by providing real historical data, which may not be new to you if you’ve studied Black History, American History, and Church History. But I appreciate the manner in which Jemar assimilates this data.

I finished the book with a mixture of hope and despair. I’m thankful for God’s true Church, the gift of repentance and forgiveness of our sins, the Holy Spirit’s abundant power to change, and Jesus’ imminent return. I was grieved because though we’ve come so far, it also feels like we have so far to go. I left asking myself, “Am I living after a pattern from scripture, or do I tinker to build a world I want?”